You might think of “cute and cuddly” when you think of cats, but in the name of Australia’s endangered species, think again.

en.wikipedia.org

Felines pose one of the biggest threats to Australia’s endangered species.

According to petsmart.com, cats probably arrived in Australia as pets of European settlers and were later deliberately introduced in an attempt to control rabbits and rodents. Cats now occupy 99% of Australia, including many offshore islands and more than 20 million feral cats are roaming the continent destroying endangered species and threatening biodiversity.

Gregory Andrews, the Threatened Species Commissioner, says feral cats currently harm the future existence of more than 100 species.

Since 1788, felines have contributed to the eradication of 29 species. Among the fallen are the desert bandicoot and the Tasmanian tiger.

“Each feral cat eats between three and 20 native animals a day,” Andrews told the Australian Broadcasting Company. “That adds up to a conservative 80 million native animals a day.”

Photo of endangered eastern quoll from DailyMail.UK

As of this year, sixteen native species including the eastern quoll (shown on the left) have been added to the endangered list.

Australia is now fighting back with full force.

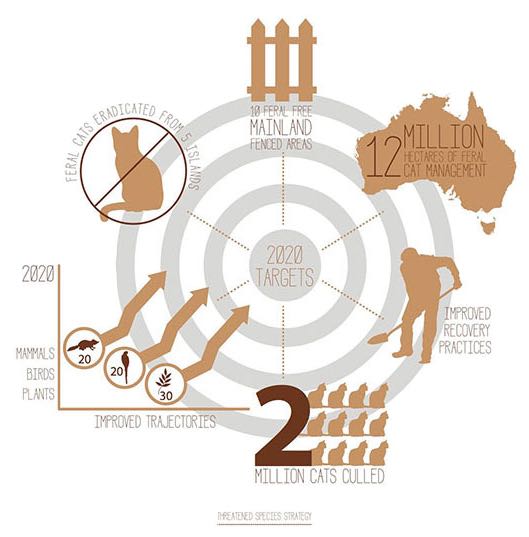

The federal government has pledged to euthanize 2 million feral cats by 2020. More than 500 population-control projects are now being conducted around the continent.

Andrews told the AAP News that animals are saved “from cruel death” for every feral cat the government kills.

Dr. Jim Radford, a conservationist with Bush Heritage Australia, called feral cats “the single biggest threat” to Australia’s endangered species.

According to the Australian government’s 2015 Action Plan for Australian Mammals, feral cats are the “most severe threat to terrestrial mammals in all threat categories.”

Greg Hunt, the country’s environmental minister, has even publically declared a war on feral cats to protect the eradication of all endangered species by 2020.

Nonetheless, Hunt insists population-control programs are humane.

“They either go to sleep or we shoot them,” Hunt says. “There are no slow deaths.”

The government aims to save 40 endangered mammals and birds as well as 30 types of native flora.

So far, the government has reported some progress.

Photo of barred bandicoot from DailyMail.UK

Andrews says some areas where cats have been targeted are seeing resurges in their bandicoot and pigmy possum juvenile populations.

But euthanizing feral cats is not the only tool in the Australian government’s arsenal. Other animals are also being trained to root them out. Dogs at the Werribee Zoo, for example, are being trained to sniff out wild cats. They will be deployed to Victoria to protect bandicoots.

For some time, the leading weapons against feral cats were poisoned baits. The largest operations utilizing this method involved aircraft that would spread more than 60,000 baits across more than 1,000-square-kilomter areas in Australia’s outback.

Endangered animals were also protected by being isolated from feral-cat strongholds and placed in cat-proof fences.

John Woinraski, author of Australia’s mammal action plan, told Vice News in July 2015 that these fences were “the only place many mammal species are secure.”

He added, “It’s an expensive operation to build those fences, so the areas that can be protected aren’t vast, but it’s currently the only effective mechanism.”

Trapping methods were also deployed to a lesser effect. Last year, it was used in Tasmania. There, feral cats had become the apex predators after facial tumor disease took a heavy toll on Tasmanian devils. Their new status brought about serious environmental and economic impact.

Photo from Australian Broadcasting Company

The Upper Meander Catchment Land Care Group tracked cat strongholds in farmland on the fringe of Tasmania’s Western Tiers.

“There are huge amounts out there,” said spokesperson Kevin Knowles in an interview with the Australian Broadest Company, last summer. “They are everywhere.”

Knowles said systematic trapping using a grid worked for clearing areas of cats for three months to a year, before cats moved back in from adjoining areas.

At the time, the government was just implementing its mammal action plan.

Ian Sauer, Immediate past president of Tamar Natural Resource Management, was calling for a national front against the threat of feral cats.

“Conservative estimates are that cats are taking 1.3 billion tonnes of wildlife across Australia every year,” he told The Australian Broadcasting Company. “The issue is big enough and I don’t think the states on their own, like Tamar NRM, can handle this problem properly. We need a concerted, national effort, so we need national co-ordination.”

National co-ordination comes at a price.

www.smh.com.au

Today, the federal government is committing $130 million to complete its mission by 2020.

Woinraski argues that the battle won’t be won by government action alone. He’s also calling for public support. Runway pets are adding to the hordes of feral cats preying on the endangered.

“Australia spends $8 billion on pets annually,” Woinraski told Vice News. “We definitely don’t spend that on conservation.”

According to government figures, Australia spent $520 million annually on conservation between 2001-2008.

What is making the offensive against feral cats particularly challenging is their abilities to reproduce rapidly.

A draft of the government’s Threat Abatement Plan for Predation by Feral Cats released in July 2015 stated “it is not feasible with current or foreseeable resources and techniques” to eradicate all feral cats.

Woinraski recommends the development and release of a “biological agent” or engineered virus to decimate the continent’s feral cat population.

“We’re kidding ourselves if we think we can eradicate them,” Dr. Jim Radford said. “It’s difficult to bait and trap them, because they’re very shy, and culling through shooting is very difficult; you can’t shoot that many cats.”

Woinraski echoes this view.

www.ifaw.org

“It won’t be possible in the next decade,” he told Vice News. “There’s some hope it’s possible over the next several decades.”

Nonetheless, some officials believe they should stay the course for the fate of the endangered species they’re protecting.

Hunt believes the current mission of wiping out 2 million feral cats by 2020 is feasible.

“We are truly lucky to share this continent with so many wonderful and distinctly Australian animals and plants,” Hunt told AAP. “It is our duty to care for them, so our bilbies, numbats, quolls and other unique flora and fauna remain a living part of our culture.”