Photo: LA Times

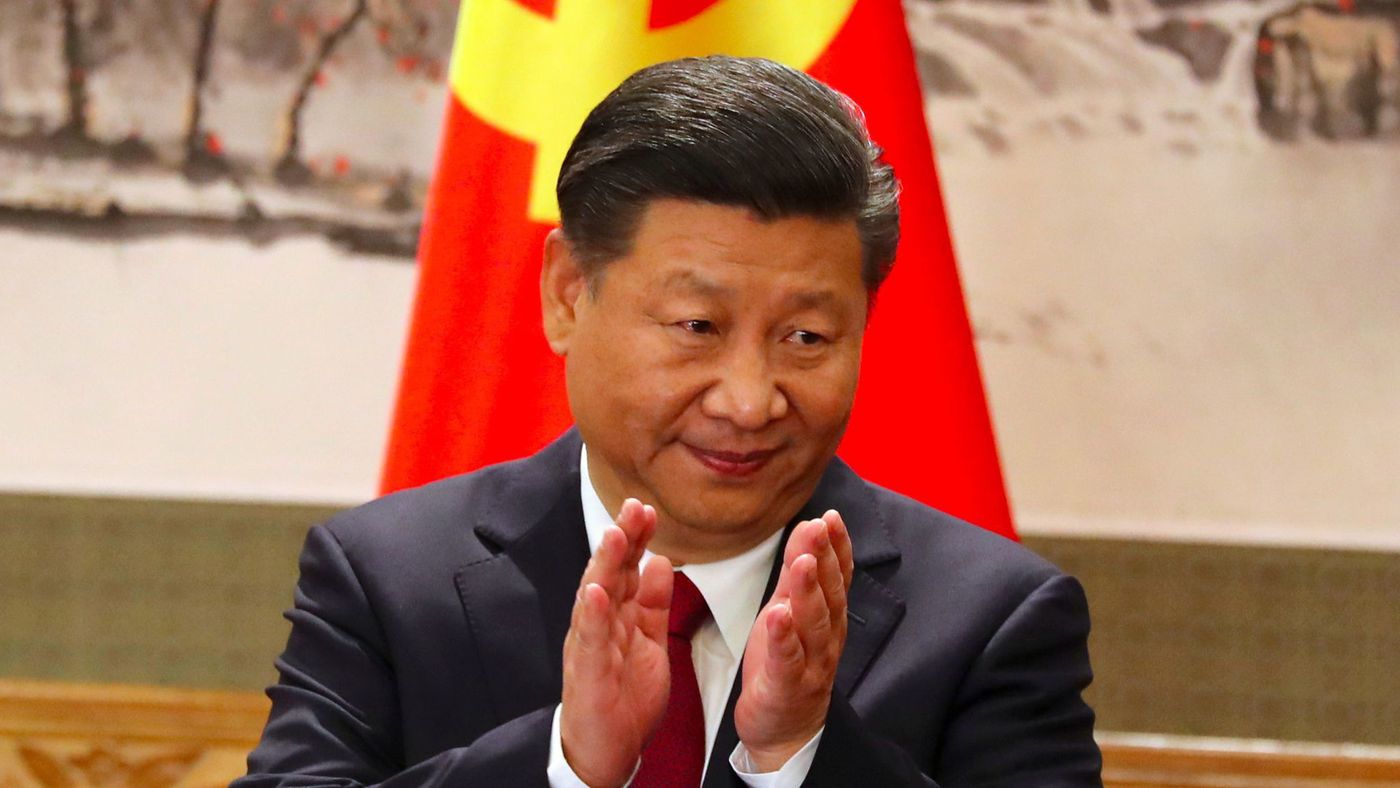

China’s ruling Communist Party has proposed scrapping constitutional term limits for the country’s president, which would give President Xi Jinping the option to stay on after the end of his second term in 2022. Critics see the move as reversing decades of efforts to create rules in China for the orderly exercise and transfer of political power.

Xi’s status as the most powerful Chinese leader in a generation was cemented at last year’s party congress, where he was given a second five-year term as general secretary.

During his first term, Mr. Xi pressed an aggressive campaign against corruption and dissent, a crackdown that has silenced potential rivals in the leadership. At the same time, many party elders, who once held intimidating influence, have died or are too old for political intrigue. Mr. Jiang is 91, and Mr. Hu, 75, has shown no appetite for taking on Mr. Xi.

China’s limits on leaders’ power have been fleeting and fragile

The position of president in China ranks below that of the head of the Communist Party and the military neither of which has legal term limits. Xi holds all three positions. Only two of Xi’s predecessors – party bosses Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin – stuck to the 10-year term limit.

Xi’s supporters argue that new leadership arrangements are needed to provide stability and continuity of leadership so that Xi Jinping can fulfill his grand ambitions of leading China into a national renaissance, and a new era of modernity, prosperity, and power.

China says that it intends to achieve basic modernization of the country by 2035, and regain its historic place at the center of world affairs. Xi also has proposed turning the Communist Party into a more disciplined and efficient organization, which reclaims its leading role in all facets of society and the economy.

The amendments are almost certain to be passed into law by the party-controlled legislature, the National People’s Congress, which holds its annual full session starting on March 5. The Congress has never voted down a proposal from party leaders.

The move alarmed advocates of political liberalization in China who saw it as part of a global trend of strongman leaders casting aside constitutional checks, like Vladimir V. Putin in Russia and Recep Erdogan in Turkey.

“Xi Jinping is susceptible to making big mistakes because there are now almost no checks or balances,” said Willy Lam, an adjunct professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who is the author of a 2015 biography of Mr. Xi. “Essentially, he has become emperor for life.”