bbci.co.uk

Less than a minute after the Super Bowl game clock hits “00:00”, the winners are presented with caps and t-shirts that declare them NFL champions. Obviously, two sets of championship gear are made in preparation for the big game but only one team will ever get to wear it. The losing team’s swag is officially banned from eBay and national TV. The NFL even claims that it’s a crime for the items to be worn on American soil, citing copyright laws.

What happens to the “illegal” clothes?

Both the NBA and MLB destroy would-be-champions’ merchandise immediately after each final game. The NFL goes a different route, donating the banned merchandise to struggling nations. Less than 24 hours after Super Bowl 50, the Panthers’ championship swag was already packaged to be shipped away by World Vision, a global relief organization.

stevedarmody.org

The items will end up somewhere in Uganda, Sienna Lion or Romania, where people don’t know anything about football and, in most cases, don’t even have running water.

hdpixa.com

Ironically enough, one of the 1,150 donated “Buffalo Bills Super Bowl Champions” t-shirts ended up on prime-time TV, in a documentary about Romanian orphans. (The Bills lost four NFL championships in a row, from 1991 to ’94.) The NFL’s community director happened to be tuning in for the documentary. She later recalled the moment it caught her eye, saying “I almost fell out of my chair.”

Why don’t the NBA and MLB donate their runner-up clothes?

Believe it or not, donating clothes isn’t always charitable. In this case, the costs of transportation, storage and distribution associated with Super Bowl merchandise add up to a hefty sum. That money could buy pay for food, healthcare and economic development, saving hundreds (if not thousands) of children. Financial analyst Saundra Schimmelpfennig explains why the NFL insists on donating the championship swag instead, in her book,“Good Intentions Are Not Enough,”:

dailymail.co.uk

Essentially, they print an equal number of Super Bowl shirts for each team, knowing they won’t be able to sell any of the shirts with the losing team’s logo. So they give the shirts to World Vision claiming a value of $20 per shirt. This is the amount that the business then deducts from their taxes for their charitable donation.

Schimmelpfennig’s main point is simple – t-shirts and caps don’t save lives.

How does the winning team get a costume change just 60 seconds after the game ends?

The manufacturer of the “Champions” gear is also responsible for handing it directly to the winners. By the time they get their Lombardi trophy, each player should be changed into their “Champions” clothing. On top of that, the losing teams’ gear must, literally, never see the light of day.

sportinglife.com

The surgical procedure was first revealed in a recent New York Times interview with Eddie White, a senior Reebok executive. When he was entrusted with sprinting across a football field holding a box of t-shirts, Mr. White was the corporation’s vice president. According to him, if one team gets a big lead early on, the second set of Super Bowl t-shirts and hats never even makes it inside the stadium. If it’s a close call, two Reebok representatives appear within arm’s reach of the field lines, each holding a box – once the game ends, one of them sprints onto the field, while the other calmly walks in the opposite direction. Mr. White makes one thing clear – regardless of the score, countless security precautions have been put in place to protect both versions of the “Champions” gear.

“Don’t worry. They’re protected as well as Elizabeth Taylor’s diamonds” – Eddie White

What’s the big deal about $20 shirts and $30 hats?

telegraph.co.uk

To the winners, showing off these shirts and caps is just as iconic as holding up the Vince Lombardi Trophy and showering their coaches with Gatoraid. In the 1997 Super Bowl, after Green Bay defeated New England, their defensive coordinator broke into tears upon holding his championship clothes for the first time. Later, he said “I’ve waited my entire life for that t-shirt and that hat.”

For the NFL, this tradition is a highly effective business strategy. Aside from ticket sales, merchandising is the largest source of profits. When it’s not football season, branded cups, key chains, posters and clothes stay in demand, bringing in $2.6 billion each year. Though there’s a long line of companies waiting to pay $ 4,000,000 for a 30-second Super Bowl commercial, those $20 shirts and $30 hats still generate a higher annual revenue.

Is the NFL ripping off American consumers?

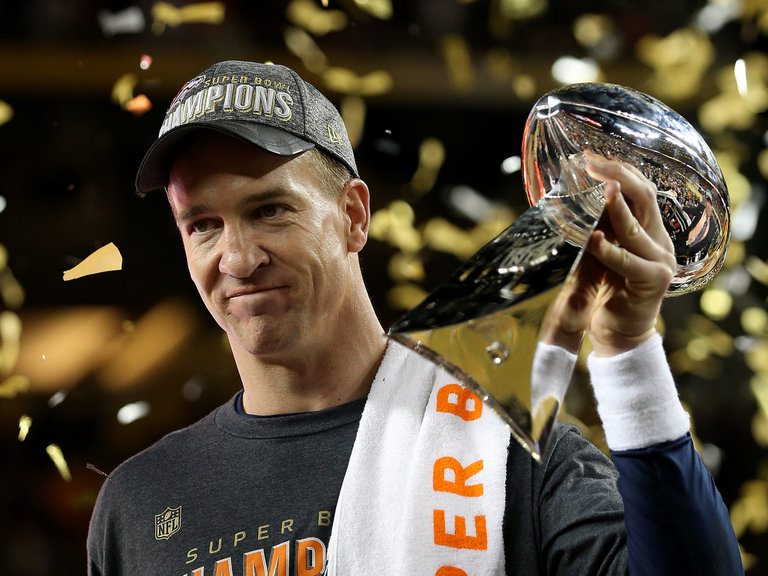

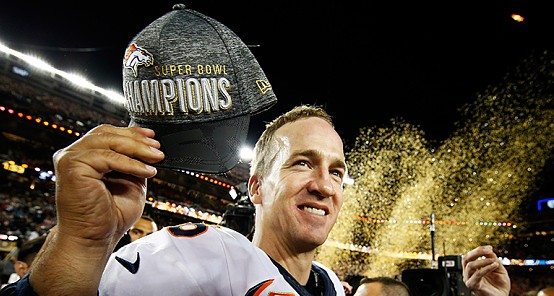

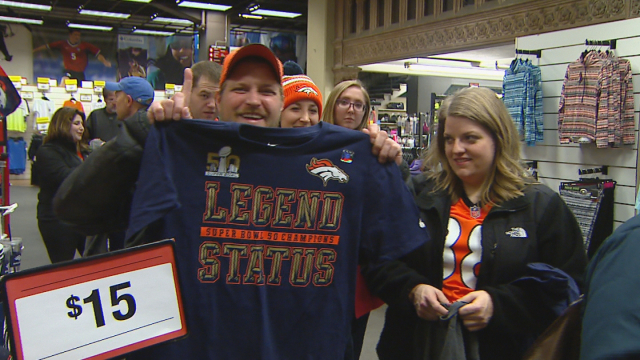

Fans lined up to buy Broncos Champions t-shirts an hour after Super Bowl 50. Photo courtesy of cbsdenver.com

The NFL turned football into an industry, where team logos are the brands and merchandise is their product. Last Sunday, after 110 million football fans tuned in to Super Bowl 50, Broncos “stock” skyrocketed. Showing Peyton Manning and the rest of the team celebrating in those t-shirts and caps is highly effective, targeted marketing at its best. The result – 2.4 million pieces of “Broncos Super Bowl Champions” merchandise sold within 72 hours.

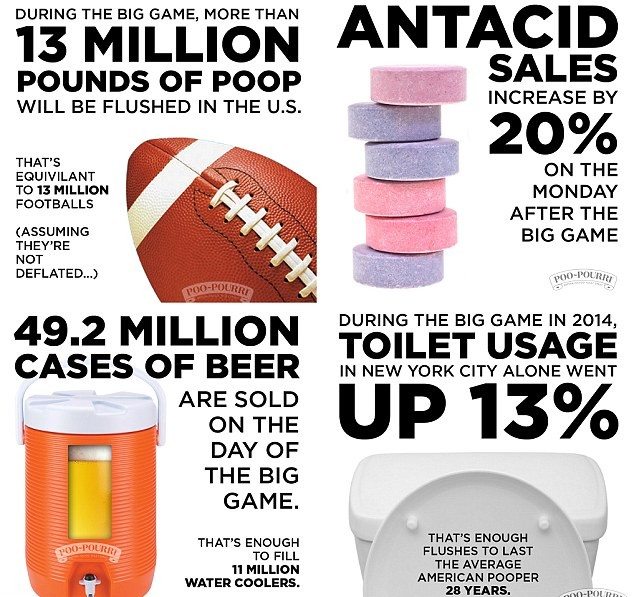

That being said, the NFL isn’t exploiting the public – it’s just focusing on the bottom line, like any other business. Plus, the Super Bowl provides a major boost for many other sectors of the economy. During the week leading up to it, Americans purchase 49 million cases of beer, 125 million chicken wings and 71 million pounds of avocados. On the following morning, Starbucks sees a 18% rise in coffee sales and 7 Eleven customers purchase 20% more antacid tablets.

dailymail.co.uk